Prepared by – Nisma për Ndryshim Shoqëror ARSIS – October 2025

The 2025 ISRD4 survey represents the first national implementation of the International Self-Report Delinquency Study in Albania, engaging high-school students aged 16–19. The study provides an unprecedented overview of youth attitudes, behaviours, and experiences related to delinquency, victimisation, and contact with the police, offering evidence on both risk and protective factors that shape young people’s resilience.

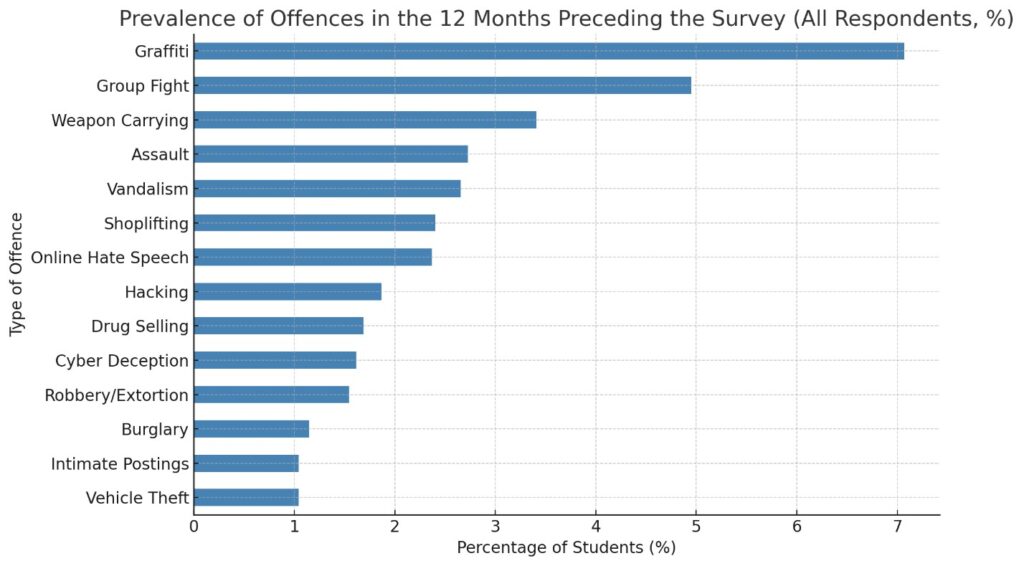

Overall, the results confirm that most adolescents engage moderate and/or low in deviant or criminal acts. The offences most commonly reported were of low severity, mainly involving peer conflict and minor property damage. Around 4–7 per cent of students had participated in a group fight, 3–7 per cent admitted to graffiti or illegal drawings, and 2–4 per cent reported carrying a weapon, primarily for self-defence. Occasional acts such as shoplifting or posting hate messages online were mentioned by only a small minority. Serious crimes such as burglary, robbery, vehicle theft, or drug selling were extremely rare, each affecting fewer than 2 per cent of respondents. Offending tended to peak among students in the middle grades (Class 11 and 12) and declined among the oldest group, suggesting that as adolescents mature, their exposure to risky or impulsive situations decreases.

New forms of digital misconduct including hacking, online deception, and sharing intimate content without consent appeared in 1–2 per cent of responses, signaling the growing relevance of cyber-safety and media-literacy education.

When it comes to victimisation, experiences were more frequent but still moderate. About 8–10 per cent of students reported being victims of personal theft, and 6–7 per cent had been bullied or threatened online. Experiences of parental violence, whether minor or serious, affected roughly 2 per cent of youth, while direct physical assault or robbery remained infrequent. Victimisation rates declined with age, pointing to the protective effects of maturity, peer awareness, and improved coping skills. Gender differences were notable. Boys were more likely to report physical and confrontational behaviours fighting, weapon carrying, or vandalism whereas girls were more exposed to relational and online victimisation, such as cyberbullying and parental conflict. These patterns call for gender-responsive prevention measures that combine emotional-regulation training for boys with digital-safety and empowerment programmes for girls.

Regional disparities were evident. Tirana and Kamëz accounted for the majority of self-reported offences and victimisation, reflecting the greater social and digital exposure typical of large urban areas. Smaller municipalities such as Çërrik, Pogradec, and Ndroq recorded sporadic cases, likely owing to closer community networks and stronger informal control.

Incidents motivated by ethnicity, religion, gender identity, or appearance were rare, but the few cases reported show that prejudice and discrimination still exist in youth settings and should be addressed through inclusive school culture and civic education.

Finally, most interactions between young people and the police were informal and preventive. In nearly half of the cases, the police informed parents; others resulted in a simple warning or school notification. Only a small fraction led to formal sanctions, indicating a preference for educational and family-based responses over punitive ones. Taken together, these findings depict Albanian adolescents as largely lawabiding and resilient, yet exposed to emerging online and relational risks. Strengthening family support, psychosocial services, and school-community cooperation will be key to sustaining youth protection and preventing future delinquency.

In Albania, a compelling narrative emerges from the available data, weaving together the attitudes, behaviors, and experiences of elementary and high school students with the complex interplay of risk and protective factors influencing youth involvement in criminal and deviant activities.

The narrative begins by acknowledging a concerning reality: while not widespread, criminal behavior among Albanian youth is a consistent and growing issue. Data highlights a rising trend in risky behaviors, including substance use. A 2015 study noted that cannabis use among 15 – 16-year-olds had risen to 7%, up from 4% in 2011, while alcohol consumption starts as early as 13 for many students. Beyond substance use, hundreds of minors are involved in crimes each year, with theft being the most common offense. Even within the classroom, deviant behavior is evident, as shown by a 2021 study revealing rampant cheating during online learning among high school students. This troubling behavior reflects a deeper disillusionment with the education and justice systems, as many young people perceive them as corrupt.

The risks driving this delinquency are multifaceted, starting within the family unit. Socioeconomic hardship, including poverty and parental unemployment, creates a stressful environment that, when combined with poor parenting and neglect, can push young people toward delinquency. Domestic violence is another significant factor, with a 2022 survey revealing that one-third of 15-year-olds had experienced physical abuse. This normalization of violence, combined with parental neglect, fosters insecure attachments and aggressive tendencies in youth.

Schools, rather than serving as safe havens, often compound these risks. Physical and psychological violence, including bullying, are common occurrences. A 2024 investigation uncovered numerous physical fights among students in schools, while around 20% of adolescents reported being bullied. The situation is exacerbated by some teachers who still resort to physical punishment, and by poor educational quality, which contributes to student apathy.

At the societal level, systemic weaknesses in child protection and justice systems further increase vulnerability. A lack of funding and coordination in child protection, coupled with cultural norms that accept violence and distrust authorities, often leaves young people without the support they need.

However, the narrative is not solely one of risk and vulnerability; it also highlights powerful protective factors and glimmers of hope. A significant turning point came with the 2017 Criminal Justice for Children Code, which marked a paradigm shift toward rehabilitation over punishment. Backed by organizations like UNICEF, this has led to specialized court procedures and community-based programs for minors.

Community and school-based programs are also proving effective. Pilot programs have successfully reduced physical discipline and peer violence in schools. Some schools have also implemented safety measures like security officers and cameras, though their effectiveness has been debated.

Ultimately, the most powerful protective factors emerge from within the youth and their social environments. A strong sense of belonging at school has been linked to lower rates of substance use and violence. By focusing on youth engagement, social integration, and parental involvement, interventions can foster personal and social development, steering young people away from at-risk situations and toward a more positive future.

This survey was conducted within the framework of the project “Building Resilience of Youth Towards Criminal Activities”, implemented under the SMART Balkans – Civil Society for Shared Society in the Western Balkans regional initiative, led by NGO Juventas (Montenegro) in partnership with Nisma për Ndryshim Shoqëror ARSIS (Albania) and the Belgrade Centre for Human Rights (Serbia). The project is implemented by the Centar za promociju civilnog društva (CPCD), the Center for Research and Policy Making (CRPM), and the Institute for Democracy and Mediation (IDM), and is financially supported by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of Norway (NMFA).

The survey in Albania was designed and implemented in accordance with the methodological framework of the International Self-Report Delinquency Study (ISRD4). The ISRD is a global collaborative research initiative aimed at producing reliable self-report data on youth offending and victimization, grounded in robust theoretical and methodological principles that inform crime prevention and youth development policies. The survey aims to collect empirical data on the attitudes, behaviours, and experiences of elementary and high school students in Albania, providing evidence on both risk and protective factors influencing young people’s involvement in or resilience against criminal and deviant activities. The questionnaire used is the standardized ISRD4 instrument, adapted and translated to reflect the cultural and educational context of Albania, and administered in accordance with the ISRD international protocol to ensure comparability with other participating countries.

Participation in the survey was strictly voluntary and anonymous. Data were collected electronically in classroom settings, with prior notification sent to schools and parents, who were allowed to decline participation. No personal identifiers were collected, and responses were treated with full confidentiality. The study adheres to the ethical standards and data protection principles of the ISRD network and Albanian legislation on the protection of personal data.

The opinions, analyses, and interpretations presented in this report are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the SMART Balkans consortium, its implementing partners, or the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The present research represents the first implementation of the International Self-Report Delinquency Study (ISRD4) in Albania, marking an important step toward building an evidence-based understanding of youth delinquency and victimisation in the country. Conducted within the regional framework of the project “Building Resilience of Youth Towards Criminal Activities”, the study aims to generate reliable, comparable, and policy-relevant data on young people’s experiences, attitudes, and behaviours related to deviant and prosocial conduct.

The general aim of the study is to collect and analyze empirical data on self-reported offending and victimization among minors, to inform prevention, protection, and rehabilitation strategies targeting children and adolescents in Albania. More specifically, the objectives of the ISRD4 survey in Albania are to:

The study distinguishes between three groups of young people:

These theoretical lenses will help interpret the complex social and psychological dimensions of juvenile behavior in the Albanian context.

By applying the standardized ISRD4 instrument and research protocol, the Albanian study provides cross-nationally comparable data with Montenegro, Serbia, and other participating countries, enriching the collective understanding of youth delinquency patterns in the Western Balkans.

The target group of the ISRD4 survey in Albania consists of high school students aged 16 to 19 years, enrolled in the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd grades of upper secondary education. This age group was selected to capture the experiences, attitudes, and behaviors of older adolescents, a developmental stage characterized by increased autonomy, peer interaction, and exposure to diverse social and online environments that may influence risk-taking and protective behaviors. The focus on upper secondary students reflects both the structure of the Albanian education system and the project’s objective to explore youth perspectives during the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Participation in the survey was voluntary and anonymous, and conducted in full compliance with ethical and data protection standards. The questionnaire was administered by trained facilitators using a codified online system, which allowed participants to access and complete the survey individually through their own digital devices, ensuring confidentiality and data integrity.

Although coordinated with schools, the survey was carried out outside regular school classes, to avoid any influence from the classroom environment and to ensure that participation remained entirely voluntary and self-directed. Students from a diverse range of high schools across different regions of Albania took part, ensuring variation by geographical area, gender, and socio-economic background. This national sample provides an important evidence base for understanding youth behavior, vulnerability, and resilience in the Albanian context and contributes to the broader international ISRD4 comparative research.

The survey in Albania was conducted in accordance with the guidelines and research protocol of the International Self-Report Delinquency Study (ISRD4) organizing committee. This ensured methodological consistency across all participating countries, including the use of a standardized questionnaire, sampling procedures based on internationally agreed principles, and uniform procedures for data coding, entry, and the transfer of anonymous data to the joint international ISRD4 database.

The general structure of the ISRD4 questionnaire consists of three main components:

The questionnaire covers eight thematic blocks with a total of over 60 questions, many of which have several sub-questions. The questionnaire is answered in the LimeSurvey survey environment using a computer or tablet within 45 minutes. The questionnaire covers the following topics:

This structure allows for a multidimensional analysis of adolescent experiences, exploring both risk and protective factors that influence young people’s involvement in or resistance to deviant behaviors. A more detailed breakdown of the topics studied in relation to offences and victimisation occurring both online and offline is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Distribution of topics covered in the ISRD4 study between offline and online experiences.

| Offline experiences | Offence | Victimization |

| Assault | X | X |

| Burglary | X | |

| Sale of narcotics | X | |

| Graffiti | X | |

| Gang fights | X | |

| Hate crime (violence) | X | X |

| Parental abuse | X | |

| Severe violence by parents | X | |

| Theft of personal belongings | X | |

| Extortion | X | X |

| Shoplifting | X | |

| Vehicle theft | X | |

| Carrying a cold weapon (knife, club) | X | |

| Experience in the online environment | Offence | Victimisation |

| Cyberbullying | X | |

| Hate speech | X | X |

| Hacking | X | |

| Sending sexually suggestive images | X | X |

| Cybercrime | X |

The ISRD4 data collection in Albania was conducted in accordance with the international ISRD4 research protocol and under the framework of the regional project “Building Resilience of Youth Towards Criminal Activities”. Data collection took place during September 2025 and involved high school students aged 16 to 19 years, enrolled in the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd grades (10-12 grade) of upper secondary education. The process followed a standardized and ethically approved methodology to ensure anonymity, data reliability, and full comparability with other participating countries.

Before the start of the survey, schools were contacted and informed about the purpose, objectives, and confidentiality procedures of the study. Participation of students was strictly voluntary, and informed consent was obtained through collaboration with school administrations. The survey was implemented using a secure, codified online system, in which each participant accessed the questionnaire via a unique access code generated for the study. This ensured both the confidentiality of responses and the integrity of data collection.

The online questionnaire was administered in Albanian language, and participants completed it individually through their own digital devices (such as smartphones, tablets, or laptops). The estimated completion time was approximately 40–45 minutes.

To maintain methodological consistency and participant confidence, data collection was supervised by a team of trained facilitators who were responsible for:

The survey environment was designed to protect privacy and encourage honesty, with participants completing the questionnaire outside regular school classes, in a calm and confidential setting, without supervision from teachers or school staff. All collected data were stored securely and transferred in anonymized format to the international ISRD4 database, contributing to the broader cross-national analysis coordinated by the ISRD network.

A total of 25 schools were invited to participate in the survey, of which 6 educational institutions declined. 19 schools, 262 classes and a total of 5237 students participated in the survey. When planning the survey, the refusals were taken into account and a larger sample was formed to ensure that the required number of young people participated in the survey.

The sampling unit of the ISRD4 survey in Albania was the school. The sampling strategy followed the international ISRD4 methodological guidelines, ensuring that the selected institutions provided adequate geographical, socio-economic, and gender representation of students across the country.

The sample consisted of public high schools enrolling students aged 16 to 19 years, corresponding to the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd grades of upper secondary education. Within the selected schools, all students from the designated grades were invited to participate in the survey. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, based on informed consent procedures agreed upon with the schools and, where required, parents or legal guardians.

In total, approximately 5237 students were invited to take part in the survey, with a completion rate of around [e.g., 57%]. After data cleaning, where questionnaires with excessive missing data, inconsistencies, or invalid responses were excluded, the final database contained [2787 students] valid responses.

As the survey targeted older adolescents, participation varied by grade, with the highest representation among 1st grade students (aged 16). Some schools allowed only partial participation from specific classes due to scheduling constraints or examination periods.

Table 2. Description of the sample of general education schools

| Region | Number of schools | Number of pupils in general size in the population 10-12 grades) reached | Estimated | Participating School sample number* |

| Cerrik | 4 | 390 | 390 | 330 |

| Kamez | 4 | 2690 | 2690 | 493 |

| Kavaje | 3 | 645 | 645 | 169 |

| Ndroq | 1 | 140 | 140 | 122 |

| Peze | 1 | 55 | 55 | 2 |

| Pogradec | 2 | 875 | 875 | 202 |

| Tirane | 3 | 2400 | 2400 | 966 |

| Vaqarr | 1 | 150 | 150 | 131 |

| Typed the code incorrectly | 0 | 0 | 0 | 372 |

| TOTAL | 19 | 7345 | 7345 | 2787 |

The national dataset therefore provides a robust and representative basis for analyzing patterns of selfreported delinquency, victimization, and protective factors among adolescents in Albania, while maintaining full comparability with ISRD4 data from other participating countries.

Table 3. ISRD-4 survey sample by gender, class, age and region

| Characteristic | No | |

| Gender1 | boy | 902 |

| girl | 1854 | |

| Class2 | 10 class | 865 |

| 11 class | 893 | |

| 12 class | 659 | |

| Age[1] | 16 y.o | 1847 |

| 17 y.o | 788 | |

| 18 y.o | 108 | |

| 19 y.o | 17 | |

| City | Cerrik | 330 |

| Kamez | 493 | |

| Kavaje | 169 | |

| Ndroq | 122 | |

| Peze | 2 | |

| Pogradec | 202 | |

| Tirane | 966 | |

| Vaqarr | 131 | |

| Typed the code incorrectly | 372 |

The prevalence of offenses was examined by asking respondents whether they had ever committed or committed any other type of illegal act. If the answer was yes, the respondent was asked to specify how many times this had been done in the last 12 months. The list of offences investigated is presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Offences covered by the ISRD 4 survey

| Offences | Questions | |

| Vandalism | Graffiti | Have you ever drawn or painted graffiti on a wall without permission in a tunnel, on a train, bus or other similar place? |

| Vandalism | Have you ever deliberately damaged anything, such as bus stops, windows (shop windows), cars, bus or train seats, etc.? | |

| Property offences | Shoplifting | Have you ever stolen anything from a shop or shopping centre? |

| Burglary | Have you ever broken into a building with the intention of stealing something? | |

| Car theft | Have you ever stolen a motorbike or car? | |

| Violence | Extortion | Have you ever used a weapon, force or threats to obtain money or other items from someone? |

| Carrying a cold weapon | Have you ever carried a cold weapon for self-defence or to attack others? (a weapon, such as a stick, club, knife or pistol) | |

| Group fight | Have you ever been involved in a group fight on the street or in another public place (e.g. shopping centre, stadium)? | |

| Assault | Have you ever beaten someone up or hurt them using a stick, club, knife or pistol so severely that they were injured? | |

| Drug dealing | Drug dealing | Have you ever sold drugs or helped someone else sell drugs? |

| Offences committed on the Internet | Sharing intimate photos | Have you ever shared intimate photos or videos of someone online who did not want others to see them? |

| Hate crimes online | Have you ever sent hurtful messages or comments on social media about someone’s race, ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation or other similar characteristics? | |

| Computer fraud | Have you ever used the internet, e-mail or social media to deceive others (e.g. phishing, purchasing worthless or illegal items | |

| Hacking | Gain control or destroy data? | |

The ISRD4 survey provides valuable insight into the prevalence and nature of self-reported offending among high school students in Albania aged 16 – 19. Overall, the data indicate that the majority of young people have moderately engaged in criminal or deviant acts, while a smaller proportion report occasional involvement in low-severity or situational behaviors, most commonly related to peer conflict or impulsive actions rather than persistent delinquency.

The most frequently reported behaviors in the 12 months preceding the survey include:

More serious offenses, such as burglary, robbery/extortion, vehicle theft, or drug selling, were rarely reported, each accounting for fewer than 2% of all responses.

The pattern of responses suggests that occasional peer-related conflicts and minor property offenses are more common among adolescents than deliberate or organized criminal acts. These forms of misconduct appear to be situational, peer-influenced, and often transient, typical of late adolescence. Emerging digital offenses such as hacking, online deception, or sharing intimate content without consent were reported by 1–2% of students, pointing to the gradual shift of risky behaviors into the online sphere. Taken together, the findings show a moderate to low level of youth offending in Albania, dominated by non-violent and episodic acts.

Figure 1. Prevalence of offenses during lifetime and in the 12 months preceding the survey (%)

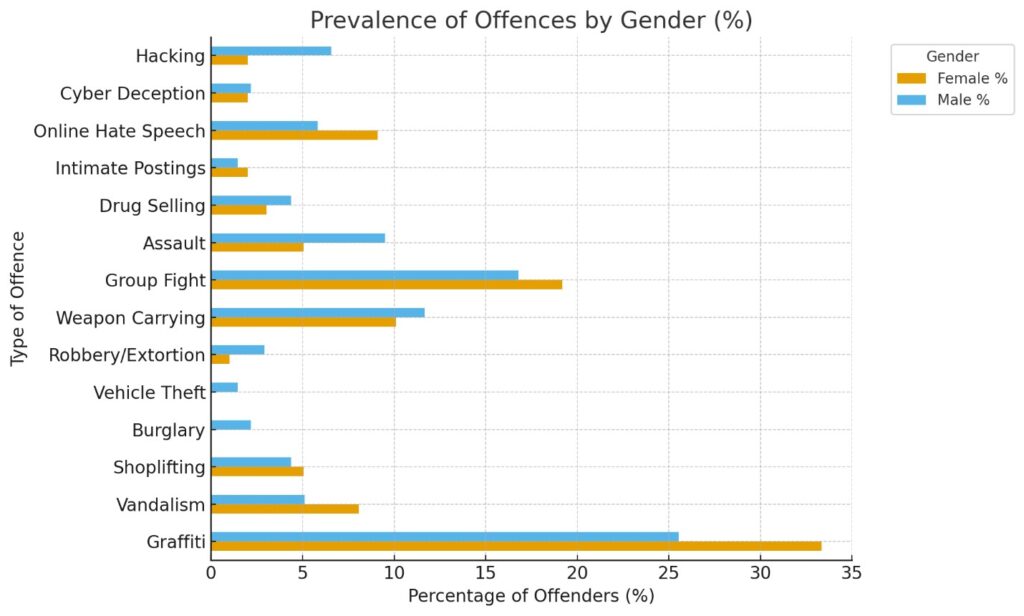

The ISRD4 findings in Albania show distinct gender differences in self-reported offending behavior among high-school students aged 16 – 19. Although the overall prevalence of delinquent acts remains low for both sexes, male respondents reported higher involvement in nearly all categories of offenses. The most visible gender gap appears in group fights, where male participation was almost twice as high as that of females, followed by weapon carrying and assault. These results align with international trends indicating that adolescent boys are more likely to engage in direct physical confrontation and risk-taking behavior.

Female respondents were comparatively more represented in non-violent and situational behaviors, such as graffiti and online hate speech, but at much lower rates than their male peers. Both groups showed very limited engagement in serious offenses such as burglary, robbery, or vehicle theft, each reported by only a few individuals.

Cyber-related acts such as hacking, online deception, or sharing intimate material were reported by both genders, though again with slightly higher frequencies among males.

Overall, the data confirm that gender remains a significant factor shaping the nature and expression of adolescent offending in Albania. Male youth tend to be more involved in physical and confrontational acts, while females report sporadic, low-severity, and often relational or online behaviors.

Figure 2. Prevalence of offenses by gender (%)

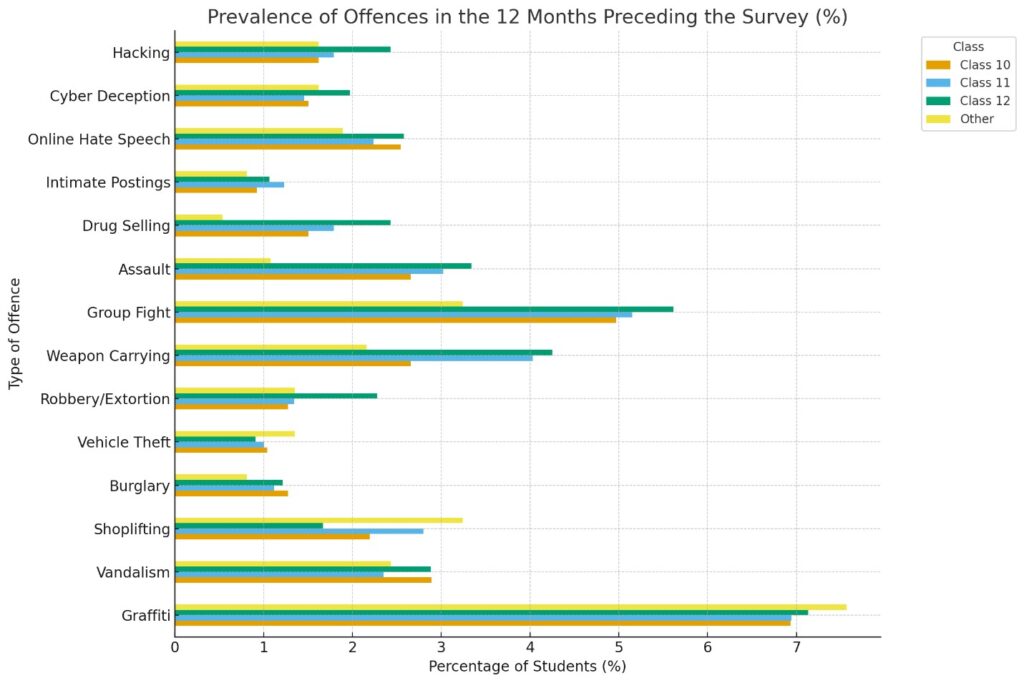

When looking at the occurrence of offenses by grade (Figure 8), it is important to analyze the occurrence of offenses in the year preceding the survey, as this indicator better reflects age differences in the commission of offenses. The results show a very clear trend: the prevalence of offenses among primary school pupils is higher than among secondary school pupils. This difference is probably related to the fact that secondary schools are attended primarily by children with better academic results and discipline.

When comparing the eighth grade with the ninth grade (Figure 8), it becomes clear that the level of offences is higher in the ninth grade in terms of drug dealing (4% and 2% respectively) and there are also some differences in sending hate messages (8% and 7%) and computer fraud (2% and 1%, respectively).

In secondary school classes, the incidence of offenses differs with age only in the case of graffiti and vandalism: 11th-grade secondary school students commit this type of offense less often than 10th grade secondary school students.

Table 5: Occurrence of offenses in the year preceding the survey by grade (%).

| OFFENSES | 10’th grade | 11’th grade | 12’th grade | Incorrect Code | Total |

| Offending (Graffiti) | 23 | 24 | 12 | 9 | 68 |

| Offending (Vandalism) | 7 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 15 |

| Offending (Shoplifting) | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 11 |

| Offending (Burglary) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Offending (Vehicle Theft) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Offending (Robbery/Extortion) | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 5 |

| Offending (Weapon Carrying) | 7 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 27 |

| Offending (Group Fight) | 17 | 17 | 8 | 1 | 43 |

| Offending (Assault) | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 19 |

| Offending (Drug Selling) | 2 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 10 |

| Offending (Intimate Postings) | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Offending (Online Hate Speech) | 6 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 18 |

| Offending (Cyber Deception) | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Offending (Hacking) | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 12 |

| Total | 76 | 88 | 61 | 19 | 244 |

Figure 3. Occurrence of offenses in the year preceding the survey by grade (%).

The regional distribution of self-reported offences highlights clear urban concentration patterns, with Tirana (42%) and Kamëz (29%) accounting for the majority of recorded incidents. These areas are characterized by higher population density and more diverse social interactions, which often correlate with increased visibility and reporting of youth-related misconduct. The most frequent offences in Tirana and Kamëz include graffiti, group fights, and weapon carrying, reflecting both peer-related conflicts and symbolic forms of expression in urban settings. Smaller municipalities such as Çërrik, Ndroq, and Pogradec reported fewer cases, typically limited to isolated incidents of group fighting or vandalism. In contrast, Kavajë and Vaqarr show minimal involvement, suggesting either lower exposure to high-risk environments or a stronger role of community supervision. Overall, the data point to a localized concentration of minor delinquent behavior in larger urban centres, where social and economic pressures are higher. The findings underscore the need for targeted community and school-based prevention programs in Tirana and Kamëz, focusing on peer conflict resolution, youth engagement, and the reduction of weapon carrying and vandalism among adolescents.

Table 6. Offenses in the last 12 months by region (%).

| OFFENSES | CERRIK | KAMEZ | KAVAJE | NDROQ | POGRADEC | TIRANE | VAQARR | Incorrect Code | Total |

| Offending (Graffiti) | 2 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 37 | 4 | 9 | 68 |

| Offending (Vandalism) | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 15 |

| Offending (Shoplifting) | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 11 |

| Offending (Burglary) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Offending (Vehicle Theft) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Offending (Robbery/Extortion) | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Offending (Weapon Carrying) | 4 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 2 | 27 |

| Offending (Group Fight) | 4 | 9 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 18 | 2 | 1 | 43 |

| Offending (Assault) | 0 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 19 |

| Offending (Drug Selling) | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Offending (Intimate Postings) | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Offending (Online Hate Speech) | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 18 |

| Offending (Cyber Deception) | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Offending (Hacking) | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 12 |

| Total | 13 | 71 | 6 | 13 | 11 | 102 | 9 | 19 | 244 |

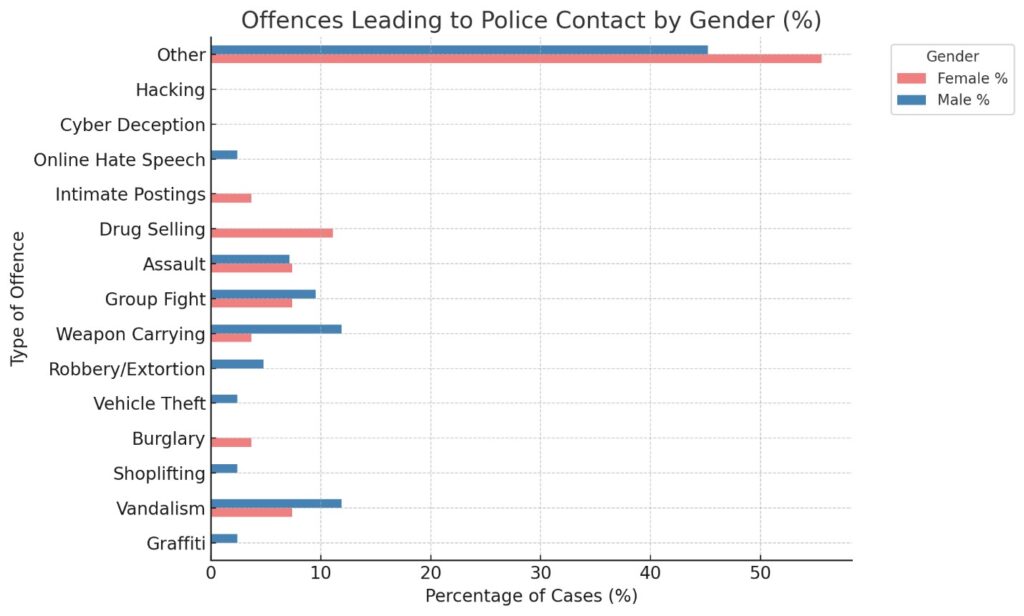

The ISRD4 data indicate that male students are more frequently involved in offences resulting in police contact compared to females. Out of 72 total cases, 58 per cent involved boys, 38 per cent involved girls, and a minimal number were from respondents identifying as non-binary or who did not disclose gender. For both genders, the offences most likely to trigger police intervention were vandalism, group fights, and weapon carrying, followed by assault and drug selling. These behaviours typically occur in public settings, where visibility and peer involvement increase the likelihood of detection and reporting.

Male offenders were overrepresented in vandalism, weapon carrying, and robbery/extortion, whereas female offenders appeared more frequently in drug-related and interpersonal incidents, such as assault and family-linked cases.

A notable portion of cases (about one-third) were classified as “other”, often referring to minor or contextspecific infractions that nonetheless resulted in some police response.

Overall, the findings suggest that gender influences both the type and the visibility of youth offending leading to police contact. Males tend to engage in acts more likely to draw public or law-enforcement attention, while females’ interactions with the police are often linked to interpersonal conflicts or social situations.

Figure 4. Types of offences for which young people had contact with the police, by gender (%)

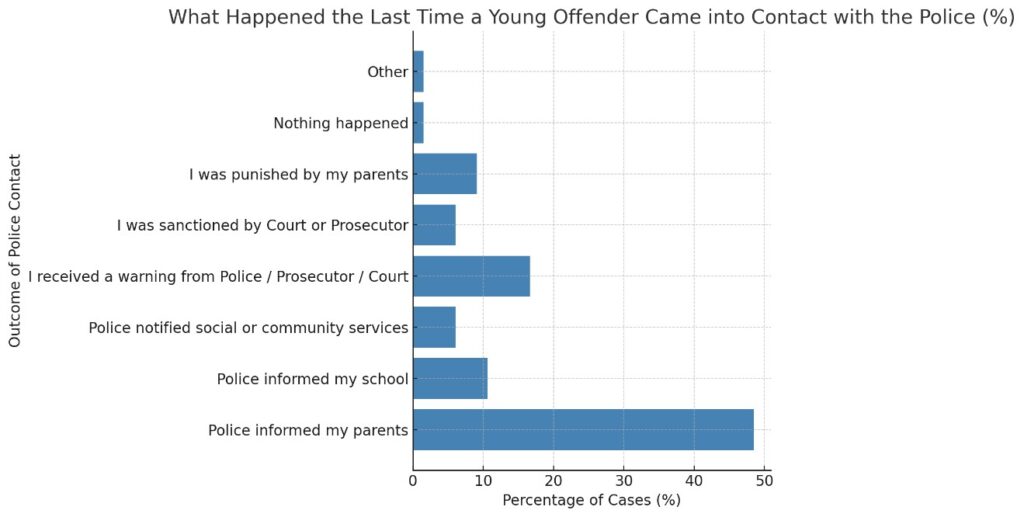

The ISRD4 data related to the contact with police reveal that when adolescents had their most recent interaction with the police, responses were largely informal and community-based, rather than judicial or punitive. The majority of cases (≈46%) resulted in the police informing the parents, followed by warnings issued by the police, prosecutor, or court (≈16%), and notifications to schools (≈10%). Only a small proportion (≈6%) involved court or prosecutorial sanctions, while police referrals to social or community services (≈6%) were also relatively rare. Very few respondents reported that nothing happened (≈1%) or that the case was categorized as “other” (≈1%).

These findings indicate that most youth–police encounter in Albania are resolved through family or educational channels, emphasizing a preventive and corrective approach rather than strict penal intervention. This pattern aligns with broader efforts in the country to divert minors from formal prosecution and manage incidents through parental engagement, school cooperation, and communitybased services.

Figure 5. What happened the last time a young offender came into contact with the police (%)

One of the objectives of the ISRD-4 survey is to identify the types of crimes that young people have fallen victim to both throughout their lives and in the last 12 months. This survey aimed to find out whether young people have been victims of robbery, assault, theft, hate crimes, threats made via social media, the distribution of intimate photos or videos via social media, hate crimes committed via social media, physical violence by parents or abuse by parents. The exact wording of the questions is presented in Table 6.

Table 6. Wording of victimization options in the ISRD4 survey questionnaire

| Category | Question |

| Robbery | Has anyone demanded money or something else from you using a weapon, force or threats? |

| Assault | Has anyone ever beaten you or hurt you using a stick, club, knife or gun so severely that you were injured? |

| Theft | Has anything ever been stolen from you (e.g. a book, money, mobile phone, sports equipment, bicycle)? |

| Hate crime | Has anyone ever threatened you with violence against you because of your race, ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation or other similar characteristics? |

| Threat | Has anyone ever threatened you on social media? social media |

| The distribution of intimate photos or video material on social media | Has anyone posted or shared that you did not want others to see? |

| Hate crime social media | Have you received derogatory messages or comments on about your race, ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation or other similar characteristics? |

| Physical violence by parents | Has your mother, father or step-parent hit or pushed you (including as punishment for some misdemeanour)? |

| Parental you misdemeanour | Has your mother, father or step-parent ever hit you hard, abused or hit you with an object (including as punishment for some)? |

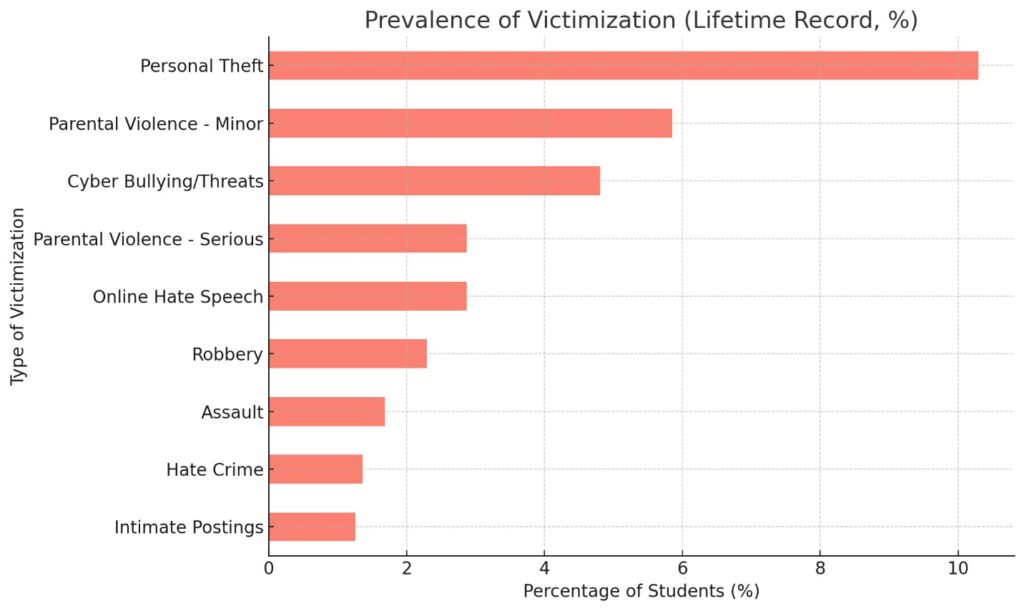

The ISRD4 findings reveal that a considerable number of Albanian adolescents have experienced some form of victimization in their lifetime, with varying intensity and nature across different types of incidents. The most frequently reported experiences were personal theft (8–10%) and cyberbullying or online threats (6–7%), followed by parental violence of a minor nature (5–6%). Reports of online hate speech (4–5%), intimate image sharing (around 2%), and hate crime (1–2%) were less common but indicate the presence of online and social tensions among young people.

Physical incidents such as robbery (around 2%) and assault (2–3%) were reported at low rates, suggesting that violent victimization remains relatively uncommon. However, experiences of domestic or parental violence, though less visible, remain a notable concern, highlighting the need for strengthened family support and counseling mechanisms. The data point to a mixed pattern of victimization, where digital and relational forms (e.g., cyberbullying, online hate speech, minor parental aggression) are becoming more prevalent than traditional physical or property-related victimization.

Figure 6. Prevalence of victimization (lifetime record, %) among all high school students participating in the ISRD4 survey in Albania

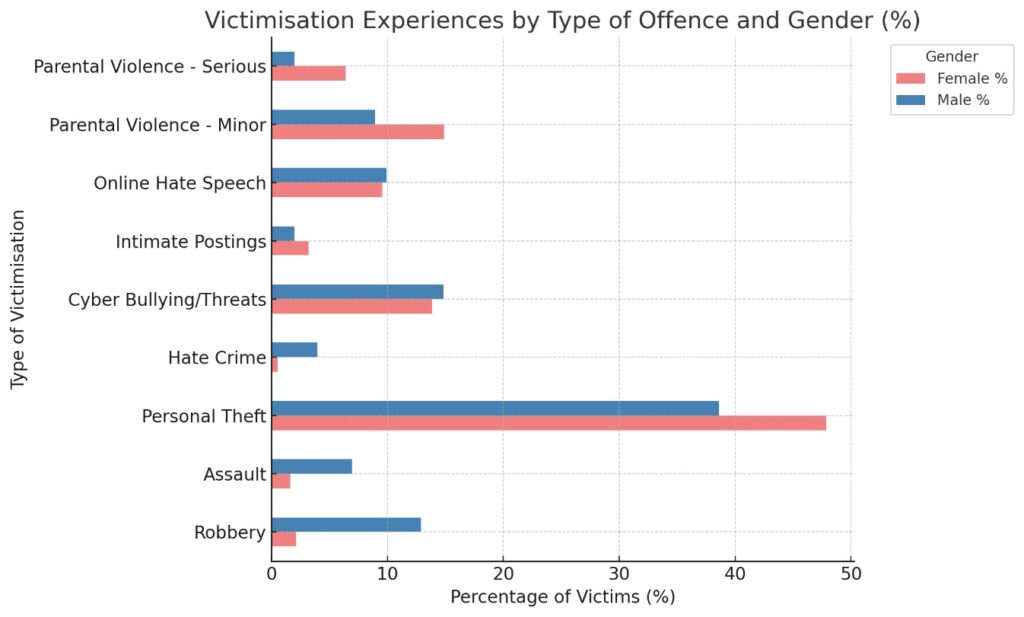

The ISRD4 data reveal notable gender differences in the types of victimisation experienced by young people in Albania. Female respondents reported higher overall rates of victimisation compared to males, particularly in personal theft, cyberbullying, and parental violence.

The data suggest that female adolescents in Albania are more affected by relational, emotional, and online forms of victimization, while male adolescents experience more direct, physical types of harm.

Figure 7. Victimization experiences by type of offense and gender (%)

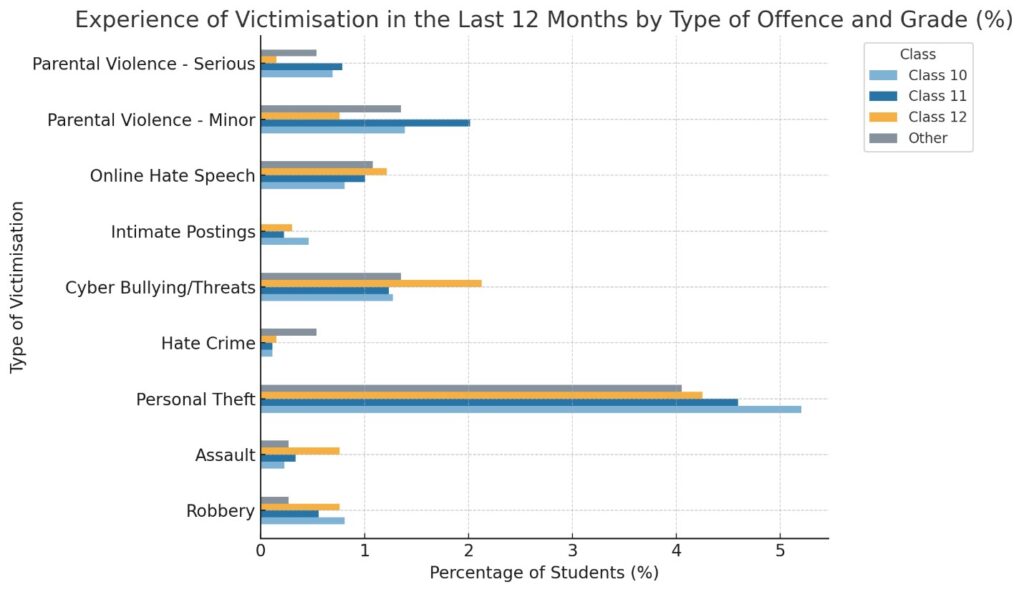

To ensure comparability, this analysis focuses on victimisation experiences reported during the year preceding the survey. Overall, the data show a declining trend in victimisation as students’ progress to higher grades, suggesting that older adolescents are less exposed to or more capable of avoiding risky situations. The most frequently reported experiences were personal theft (5–7%) and cyberbullying or online threats (1–2%), followed by minor parental violence (1–2%). Other forms of victimisation, such as robbery, assault, online hate speech, and serious parental abuse, were reported by fewer than 1% of respondents across all grades.

Students in Class 10 reported slightly higher levels of victimisation overall, particularly regarding personal theft and parental violence, while rates among Class 12 students were the lowest. This may indicate that as adolescents mature, they develop stronger social awareness, self-control, and risk-avoidance strategies.

Although the prevalence of online victimisation remains moderate, the persistence of cyberbullying and online hate speech points to the need for continued education on digital safety, empathy, and responsible online behaviour.

The findings suggest that while traditional forms of victimisation (e.g., theft, assault) are relatively rare, psychological and digital forms persist among younger students. Strengthening preventive education, counselling support, and parent school cooperation remains key to ensuring the protection and well-being of all students.

Figure 8. Experience of victimisation in the last 12 months by type of offence and grade (%).

The regional analysis shows that Tirana stands out clearly with the highest number of self-reported victimisation cases (around 56% of all reported incidents), followed by Kamëz (14%) and Çërrik (4%). Smaller municipalities such as Ndroq, Kavajë, Pogradec, and Vaqarr recorded only isolated incidents, representing a limited share of total cases. The higher rates in Tirana and Kamëz may reflect both larger population size and greater social diversity, which typically increase exposure to interpersonal conflict, theft, and online harassment. Within these urban areas, personal theft and cyberbullying were the most frequent experiences, while incidents of assault and parental violence also appeared slightly more often than in other regions. In smaller or more rural communities like Ndroq, Pogradec, and Vaqarr, the number of victimisation cases was minimal, possibly due to closer community ties and lower anonymity, which tend to reduce the likelihood of youth victimisation. Overall, the findings reveal that urban environments show higher exposure to victimisation, particularly related to property theft and online aggression, while rural and smaller municipalities display lower rates but still face challenges related to domestic or parental violence.

These patterns highlight the need for targeted prevention programs in Tirana and Kamëz focused on digital safety, conflict resolution, and family support, alongside community awareness initiatives in smaller regions to strengthen youth protection systems.

Table 7: Number of victims in the last 12 months by region

| VICTIMIZATION | CERRIK | KAMEZ | KAVAJE | NDROQ | POGRADEC | TIRANE | VAQARR | Incorrect Code | Total |

| Victimization (Robbery) | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 18 |

| Victimization (Assault) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

| Victimization (Personal Theft) | 4 | 20 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 70 | 3 | 16 | 129 |

| Victimization (Hate Crime) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Victimization (Cyber Bullying/Threats) | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 2 | 5 | 41 |

| Victimization (Intimate Postings) | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Victimization (Online Hate Speech) | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 4 | 28 |

| Victimization (Parental Violence – Minor) | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 24 | 1 | 5 | 40 |

| Victimization (Parental Violence – Serious) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 1 | 2 | 16 |

| Total | 13 | 40 | 13 | 11 | 8 | 166 | 9 | 36 | 296 |

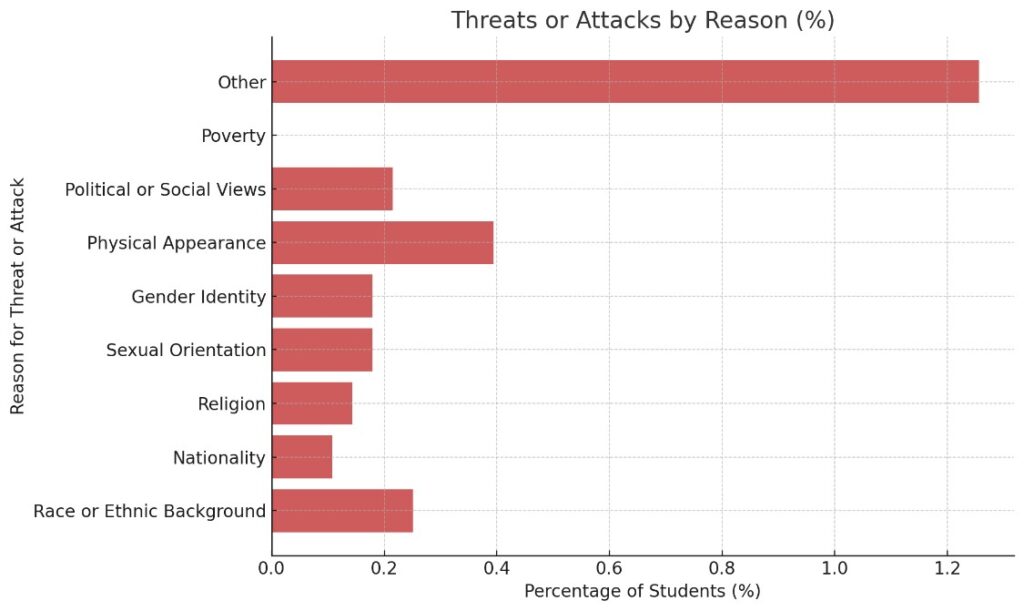

The data show that incidents of threats or attacks linked to personal or social identity factors were relatively rare among Albanian high school students, with only a few students across all classes reporting such experiences.

Across the entire sample, the most commonly cited reasons for threats or attacks were:

The category “Other” (≈1.3%) suggests that students also reported incidents motivated by additional, unspecified personal differences. Overall, these findings point to low but notable levels of hate-motivated or discriminatory experiences, mainly linked to visible or social identity traits.

Far fewer cases were linked to religion, nationality or poverty, indicating that hate-motivated aggression among youth in Albania is sporadic and not widespread.

Notably, students in Class 12 reported slightly higher experiences of hate-motivated threats (particularly related to race and physical appearance), possibly reflecting broader social interactions and online exposure typical of older adolescents. In contrast, Class 10 and 11 students reported fewer incidents overall, suggesting a lower level of direct involvement in intergroup conflicts.

The findings indicate that appearance-based discrimination and peer conflict over visible differences remain the most sensitive issues among adolescents, followed by ideological disagreements and gender identity-based intolerance.

Figure 9. Main causes/themes of different types of offline and online hate crimes (%).

The results show that reports of parental physical violence or abuse decrease with age and grade level.

If you note any form of abuse to children during an activity or work supported by Nisma për Ndryshim Shoqëror ARSIS, please report immediately at: initiative.arsis@gmail.com